I mentioned Penguin’s new edition of Bruno Schulz (THE STREET OF CROCODILES AND OTHER STORIES) in a post a few weeks ago. I hadn’t yet got a copy of it at that point, but have now, and just read David Goldfarb’s extremely informative introduction on the subway this morning (my attention interrupted only by the large swinging shoulder bag of a rude, and subsequently much ruder, passenger standing in front of me…).

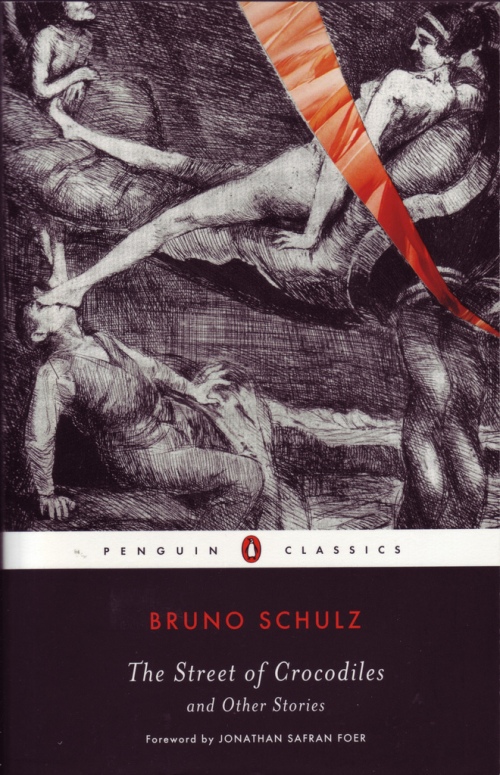

First of all, the book (which is now in the Penguin Classics list) looks great. I’m delighted that they chose to use this (somewhat altered) image of Schulz’s on the cover: the artist masochistically in thrall to the demonic woman…

Even if you already have earlier editions of Schulz’s SANATORIUM UNDER THE SIGN OF THE HOURGLASS and THE STREET OF CROCODILES—which were translated by Celina Wieniewska in the early 1960s and republished in Penguin’s wonderful “Writers from the Other Europe” list in the 1970s and 1980s—this volume is worth having, too: not only because it includes the previous books together with Walter Arndt’s translations of three other stories (“The Republic of Dreams,” “Autumn,” and “Fatherland”) which first appeared in the 1988 Letters and Drawings of Bruno Schulz, but—and I think this must be a very rare thing—because of the introduction.

What is so good about Goldfarb’s introduction? For starters, it’s well informed, based on extensive research, and there’s not an ounce of fluff in it. He efficiently contextualizes Schulz the author against the backdrop of interwar Polish Galicia and in relation to contemporary Polish avant-garde circles and the contours of his own twin careers (as both graphic artist and writer). He also places Schulz’s work in broader Polish and Central European literary contexts and in terms of the Polish language, making sense of Schulz’s poetic interest in myth and form and his use of different linguistic modes and vocabulary. Goldfarb’s interpretation of the Austro-Hungarian bureaucratic Latinisms in Schulz’s stories, for instance, sheds considerable light on matters that are completely off-limits to readers of Wieniewska’s English translation (and that probably no other English translation would be able to capture either, though who knows: there isn’t one). This reading of the word panoptikon is particularly incisive:

The term panopktikon, familiar to readers of Michel Foucault as Jeremy Bentham’s ideal reformatory where prison cells are arranged in a circle around a central guard tower, but here [in Schulz’s prose] referring to a circus side show, appears as a word that by virtue of the power of Latin to dignify the object described, in fact degrades its referent. Like P.T. Barnum’s famous sign, ‘This way to the egress,’ the Latin term is party to a kind of sham, but that sham is just the sort of ‘degraded reality’ that fascinates Schulz.

I’m also grateful for Goldfarb’s reading of the fairly untranslatable Polish word pałuba, which I had no idea was implicated in Schulz’s work (it is the title of Karol Irzykowski’s influential 1903 modernist novel).

A particularly poignant symbol of the mythic potential of all matter in Schulz is the figure of the pałuba. Pałuba is a word so untranslatable that Celina Wieniewska cannot settle on a single English word for it, and sometimes simply passes it over. One scholar of Schulz, Jerzy Jarzębski, has said that pałuba is a Polish word that must be translated into Polish every time it is used. In the relevant sense, it might be translated as ‘hag’ or ‘witch,’ or it could refer to an effigy or doll in the form of a hag.

Goldfarb situates Schulz’s work not only in these Polish linguistic and literary contexts but in relation to the English fellow mythicist William Blake and with regard to the Polish-Jewish author-artist’s influence on his inheritors, whom he divides into two groups: Polish and other Eastern European artists like Tadeusz Kantor and Danilo Kiš, and Jewish writers like Philip Roth, Cynthia Ozick, and David Grossman (whose relation to Schulz, Goldfarb suggests, is largely mediated by his biography). Interestingly, drawing on research by Canadian writer Norman Ravvin, he also points to a passage in Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh that reads like a calque of Schulz transposed to Andalusia.

Evidently this new edition was originally meant to be furnished with a foreword by Susan Sontag. There was also some talk about getting a new translation for it, but in the end Penguin went with Celina Wieniewska’s again. Wieniewska is so little known that all they have to say about her is that she “was awarded the 1963 Roy Publishers Polish-into-English prize for her translation of The Street of Crocodiles.” Roy Publishers, as I recently learned from Benjamin Paloff, was the wartime and postwar reincarnation in New York of Wydawnictwo Rój, Schulz’s publisher in interwar Poland—a Polish equivalent of the Schocken Book story. As for Wieniewska, she was the major postwar British translator from Polish. I’d like to find out more about her, and will post here when I do.

I’m only 70 precious pages into “Street of Crocodiles” and haven’t read any forewords or introductions, but the more I read the more I was impressed not just with Shulz’s obvious genius but with the translator’s brilliance. This is the second Polish-translated author I’ve read recently, the first being Withold Gombrowicz, where those translations may have left a lot of English-speakers out of the fun, but only because of Gombrowicz’s puns and wordplay. Wieniewska’s translation of Shulz, on the other hand, seems to have hit it out of the park. So vivid! So mesmerizing! And such richness of vocabulary! How could anyone have improved on it, I wonder. And it couldn’t have been easy. Wherever she is, my hat is off to her.

Alas, those who know a little about Polish realise that CW’s translation is little more than a hack job, sorry to say. It was contracted by Schulz’s last heir who didn’t check its quality. There are many omissions, and typos, but worse there are additions not in the original because Wieniewska thought, as she says in her introduction, that English cannot support such poetic Polish! Prof